By Zach Boakes, National Research and Innovation Agency of Indonesia, and Tries Blandine Razak, IPB University

Over the past 20 years, coral reef restoration has seen unprecedented growth worldwide. From Indonesia to the Caribbean, thousands of projects have been launched with the goal of “saving” coral reefs — often by planting coral fragments or building artificial reef structures.

As scientists who have worked on both natural and restored reefs for decades, we’ve watched this movement grow with hope and admiration. Yet we’ve also noticed that a crucial piece is missing.

In our new paper, published in the journal Restoration Ecology, we argue that most restoration programs focus their efforts on increasing coral growth, but rarely ask whether the reef is actually functioning as a living ecosystem.

As reef restoration continues to attract substantial interest and millions of dollars of funding globally each year, our paper calls for a major rethink of how reefs should be restored.

Ecosystem functioning: the missing piece in coral reef restoration success

A large portion of reef restoration programs measures their progress using basic indicators such as coral cover and growth. Collecting data on these metrics is relatively simple — but they only tell part of the story.

Life on a coral reef is sustained by the constant flow of energy and nutrients — driven not only by corals, but also by the interactions among other reef organisms such as fish, sponges and algae.

Scientists call this “ecosystem functioning” — the transfer and retention of energy, nutrients, and inorganic materials through living reef organisms.

Our paper argues that a large number of reef restoration programs prioritize approaches that produce near-immediate, short-term results — generally through the transplantation of fast-growing, branching corals.

While the outcomes of these efforts may look impressive at a first glance, we point out that in the long-term they often lack diversity, habitat complexity and stable populations of functionally important flora and fauna.

As a consequence, these approaches are unlikely to perform the same functional processes as natural reefs. Coral restoration is often branded as a solution that “save reefs.” Yet in reality, many offer only short-term fixes that divert attention from the primary drivers of reef decline — most notably, climate change.

With substantial funding and rising interest in coral reef restoration, the next generation of programs must refocus their efforts on the ultimate goal of creating ecologically functional reefs.

We propose three main steps to achieve this:

1. Measure ecosystem functioning on reefs

Long-term monitoring is seldom incorporated in reef restoration projects, with over 60% of programs reporting less than 18 months of monitoring data. Moreover, among those that do conduct monitoring, most focus only on simple metrics such as coral growth, while few collect data can be used to meaningfully assess ecosystem functioning.

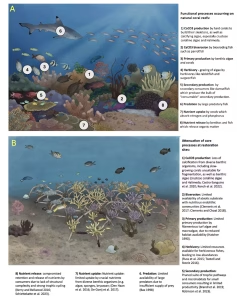

The good news is, quantifying ecosystem functioning on reefs is not as difficult as we once thought. Our paper explains, step by step, how eight key functional processes can be measured on reefs. While the full details can be found in our study, below we present an infographic that explains the basics.

Implementing these steps in reef restoration monitoring programs will be essential for determining whether, and to what extent, such efforts contribute to supporting ecosystem functioning.

2. Climate change must be a key consideration

Many restoration projects still focus their efforts on fast-growing branching corals such as Acroporidae, as they produce near-immediate results. However, these corals are some of the most sensitive to heat stress, and as oceans continue to warm due to climate change, entire restoration sites may die from future bleaching events.

We suggest programs implement transplantation of a more diverse mix of corals, including ones which may be more tolerant to heat stress, such as Platygyra daedalea.

However, if global warming continues on its current trajectory, many coral reefs are likely to experience severe decline by the end of this century. Even some of the most tolerant coral species may not withstand the threats posed by climate change.

We propose that reef restoration efforts should place greater emphasis on maintaining the processes of ecosystem functioning. This approach should help to ensure that, even if corals themselves fail to recover, restored reefs will still be able to support certain key functions — which are ultimately what make them ecologically and economically valuable.

3. Identify and protect the unsung heroes of the reef

As we show in Figure 1, from sponges to fish, there is a large suite of reef organisms that quietly keep reefs alive by performing key functional processes. These species rarely feature in restoration plans, yet without them, a reef can’t function.

We encourage reef restoration and management programs to identify and protect these unsung heroes of the reef.

Our study was not written to criticize restoration work — we share the passion of giving these precious ecosystems a fighting chance — but to make those efforts effective in the long-term.

Too often, reef restoration is seen as a sprint to cover the seabed with coral as fast as possible. In reality, it’s a marathon of rebuilding the complex web of relationships that sustain the entire reef. Restoration efforts must take this long-term functional perspective into account in future planning and management, and ensure that program design and implementation truly maximize ecological value.![]()

Zach Boakes is a postdoctoral research fellow at the National Research and Innovation Agency of Indonesia (Badan Riset dan Inovasi Nasional/BRIN) and Tries Blandine Razak is a researcher in the School of Coral Reef Restoration at IPB University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. Banner photo: A diver collects data on a coral reef in Indonesia (Fakhrizal Setiawan, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons).

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. To support The Invading Sea, click here to make a donation. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at nc*****@*au.edu.