By Aimee Gabay, Mongabay

Plans to relocate an Indigenous community from a tiny Caribbean island off Panama to the country’s mainland to escape rising seas have been delayed due to administrative issues, previous COVID-19-related complications and poor budgeting. Residents say the government has failed to integrate traditional and local knowledge in the relocation and site development plans.

President Laurentino Cortizo told residents of the Indigenous Guna that the new site would be completed by Sept. 25, 2023. But no one has been given keys yet and the site has no basic services, such as water or sewage disposal. According to Erica Bower, a climate displacement researcher at Human Rights Watch, the Panamanian Ministry of Housing and Territorial Planning told HRW that the houses would be ready on April 4, but that deadline was not met.

The relocation project, which involves building 300 houses on Panama’s mainland for 1,300 Guna from Gardi Sugdub, one of 365 islands that form part of the Guna Yala archipelago, was first proposed by the island communities in the 1990s, when community leaders began to raise concerns about rising sea levels and overcrowding.

“Because of the climate changes taking place in the world, the islands of Guna Yala are more sensitive,” Atencio López Martínez, a Guna lawyer and adviser to the General Congress of Guna Yala, told Mongabay. “They are more prone to flooding and that’s why communities from Gardi Sugdub have decided to move before catastrophic events occur.”

The Guna people of Gardi Sugdub aren’t alone. Thirty other communities in Panama and more than 400 communities around the world have planned relocations similar to this one due to hazards such as floods, sea-level rise and other climate-related impacts. In Latin America and the Caribbean, for example, more than 1.6 million new displacements were recorded in 2021, and some estimates warn this could rise to 17 million by 2050.

According to Anelio Merry López, communications coordinator of the General Congress of Guna Yala, the Guna peoples first inhabited the islands around 200 years ago, arriving there from the dense jungle of what today is the Darién region on Panama’s southern border with Colombia. Driven by conflicts with Spanish invaders, missionaries and other Indigenous groups, as well as epidemics of mosquito-borne illness that threatened to wipe out their population, they traveled to Gardi Sugdub, where they flourished because of the abundance of seafood.

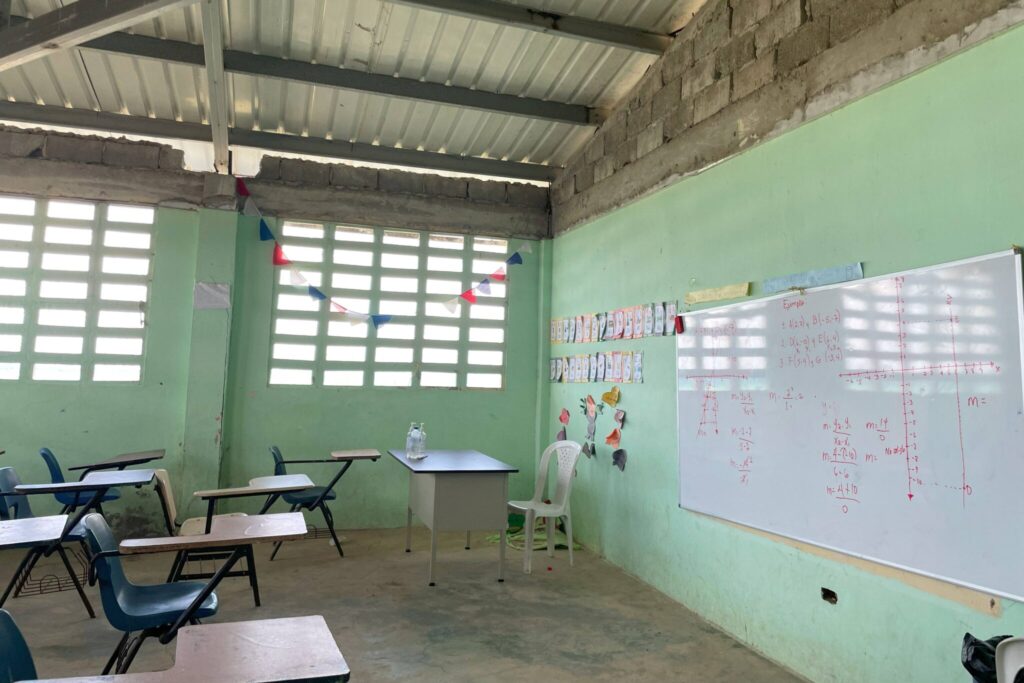

In 2010, a Guna-led committee was formed to kick-start the relocation process and secure a new home for the community. During this time, the government promised them a new school, financed by an Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) loan, and a new hospital, both to be completed by 2014. According to HRW, the incomplete hospital building has been abandoned and the school is still under construction.

Panama’s Ministry of Housing and Territorial Planning, the Ministry of Environment and the Ministry of Indigenous Affairs didn’t respond to Mongabay’s requests for comment.

According to a recent report by Panama’s Ministry of Environment, the average sea level is expected to rise by 27 centimeters (nearly 11 inches) along the country’s Caribbean coast by 2050. Gardi Sugdub residents have already started experiencing the effects of these impacts, reporting tidal flooding events that have increased in intensity and duration since the 1990s, when scientists first began to release reports on the issue. HRW recently reported that residents’ homes and belongings, including furniture, have been damaged in the past due to extreme weather events and slower-onset erosion and salinization.

Meanwhile, the lack of space on the island, roughly the size of five soccer fields, means there’s little room to relocate from the rising sea levels, which community members cite as one of the primary reasons for the move. “In recent years, the population has increased, which makes our islands very saturated,” López said.

While some residents say they’re excited to move, others express concern about the changes that will come with relocation. One particular worry is about the houses themselves, which are small and built from concrete. Traditional Guna houses are made from bamboo and built for large, extended families of up to 15 people. These Guna houses are cooler because they allow air to circulate freely, offering families respite from temperatures of up to 35° Celsius (95° Fahrenheit) that persist here throughout the year. López told Mongabay the government didn’t ask them what kinds of houses they wanted.

Martínez raised concerns about the socioeconomic repercussions of the relocation, given that the island Guna live primarily off fishing, while their new home is a 30-minute walk from the sea, closer to Panama’s jungle interior. “Now we are going to depend a lot on canned food from supermarkets,” he said.

“Panama needs to develop a policy on rights-respecting community-led relocation,” Bower said, adding that community voices need to be involved in all stages of the planning process, including home design.

Many countries “don’t have models for what rights-respecting relocation really looks like,” she added. “What we’ve learned from Gardi Sugdub is that this [process] is slow, it is hard and it’s even slower and harder to do well with community leadership front and center at all stages. But a policy needs to be put in place with adequate funding to support that.”

Mongabay is a U.S.-based nonprofit conservation and environmental science news platform. This piece was originally published at https://news.mongabay.com/2024/04/panama-delays-promised-relocation-of-sinking-island-community/.

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu.