By Courtney McGinnis, Quinnipiac University

The problem with climate change isn’t just the temperature – it’s also how fast the climate is changing today.

Historically, Earth’s climate changes have generally happened over thousands to millions of years. Today, global temperatures are increasing by about 0.36 degrees Fahrenheit (0.2 degrees Celsius) per decade.

Imagine a car speeding up. Over time, human activities such as burning fossil fuels have increased the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. These gases trap heat from the Sun. This is like pressing the gas pedal. The faster the driver adds gas, the faster the car goes.

The 21st century has seen a dramatic acceleration in the rate of climate change, with global temperatures rising more than three times faster than in the previous century.

The faster pace and higher temperatures are changing habitat ranges for plants and animals. In some regions, the pace of change is also throwing off the delicate timing of pollination, putting plants and pollinators such as bees at risk.

Some species are already migrating

Most plant and animal species can tolerate or at least recover from short-term changes in climate, such as a heat wave. When the changes last longer, however, organisms may need to migrate into new areas to adapt for survival.

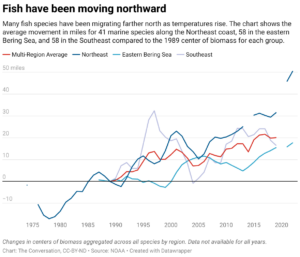

Some species are already moving toward higher latitudes and altitudes with cooler temperatures, altering their geographic territory to stay within their optimal climate. Fish populations, for example, have shifted toward the poles as ocean temperatures have risen.

Pollinators such as bees can also shift their ranges.

Bumblebees, for example, are adapted for cooler regions because of their fuzzy bodies. Some bumblebee populations have been disappearing from the southern parts of their geographic range and have been found in cooler regions to the north and in more mountainous areas. That could increase competition with existing bumblebee populations.

Plants and pollinators can get out of sync

Plants and their pollinators face another problem as the rate of climate change increases: Many plants rely on insects and other animals for seed and pollen dispersal.

Much of that pollen dispersal is accomplished by native pollinators. About 75% of plant species in North America require an insect pollinator – bees, butterflies, moths, flies, beetles, wasps, birds and bats. In fact, 1 in 3 bites of food you eat depend on a pollinator, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

So, even if a species successfully migrates into a new territory, it can face a mismatch of pollination timing. This is known as phenological mismatch.

During the winter, insects go into a hibernation known as diapause, migrate or take up shelter underground, under rocks or in leaf litter. These insect pollinators use temperature and daylight length as cues for when to emerge or when to migrate to their spring and summer habitats.

As the rate of climate change increases, the chances of a timing mismatch between pollinators and the plants they pollinate rise.

With an increase in temperature, many plants are blooming earlier in the spring. If bees or other pollinators emerge at their “normal” time, flowers may already be blooming, reducing their chance for pollination.

If pollinators emerge too early, they may struggle to survive if their normal food sources are not yet available. Native bees, for example, rely on pollen for much of the protein they need for growing and thriving.

Wild bees are emerging earlier

This kind of shift in timing is already happening with bees in the U.S.

Studies have shown that the date wild bees emerge in the U.S. has shifted by 10.4 days earlier over the past 130 years, and the pace is accelerating.

One study found wild bees across species have been changing their phenology, or timing of seasonal activities, and over the past 50 years the emergence date is four times faster. That means wild bees were emerging roughly eight days earlier in 2020 than they did in 1970.

This trend of earlier emergence is generally consistent across organisms with the accelerating rate of climate change. If the timing mismatches continue to worsen, it could exacerbate the decline of pollinator populations and result in inadequate pollination for plants that rely on them.

Pollinator decline and inadequate pollination already account for a 3% to 5% decline in global fruit, vegetable, spice and nut production annually, a recent study found.

Without pollinators, ecosystems are less resilient − they are unable to absorb disturbances such as wildfires, adapt to changes, and recover from environmental stressors such as pollution, drought or floods.

Managing climate change

Pollinators face many other risks from human activities, including habitat loss from development and harm from pesticide use. Climate change adds to that list.

Taking steps to reduce the activities driving global warming can help keep these species thriving and carrying out their roles in nature into the future.![]()

Courtney McGinnis is a professor of biology, medical sciences and environmental sciences at Quinnipiac University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. Banner photo: A bee pollinating a flower (iStock image).

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. To support The Invading Sea, click here to make a donation. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at nc*****@*au.edu.