By Tony Murray, James Dunbar and Madeleine Hirsiger Carr

Florida’s Big Bend is a vast area of locations with archaeological, cultural, ecological and geological significance. At the Aucilla Research Institute conference in Monticello in October, the importance of combining these places under one overarching site was presented. Such a concept is recognized in the UNESCO World Heritage Site program.

The program includes more than 1,200 locations around the world with “outstanding universal value to humanity” due to their cultural and natural significance. Being designated a World Heritage Site provides benefits such as stronger support for conservation efforts, increased tourism and enhanced protection.

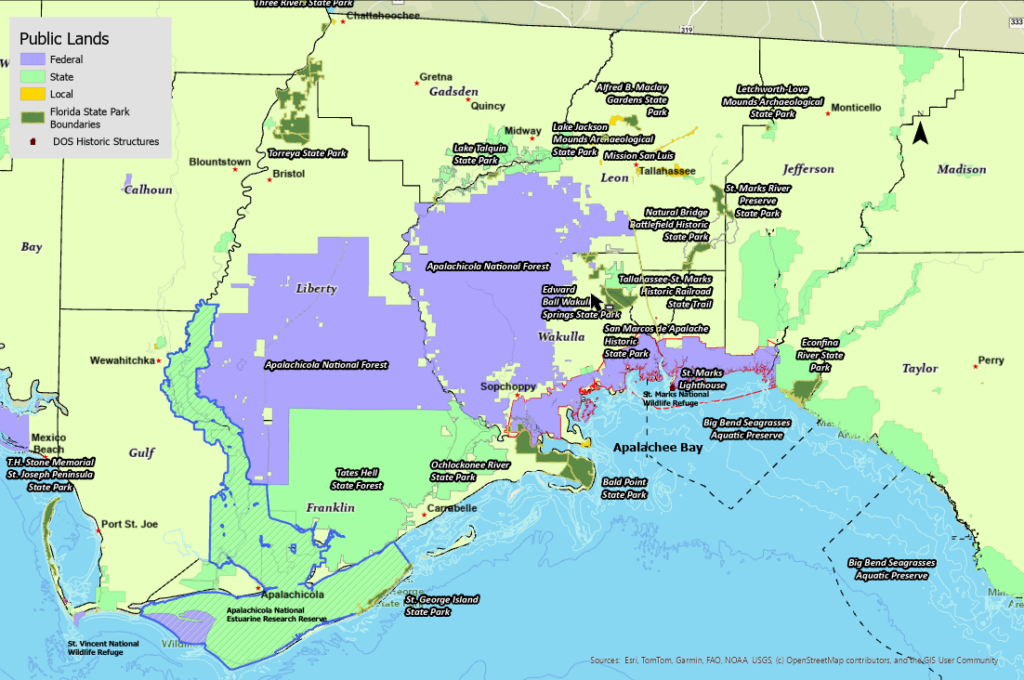

The Big Bend Coastal Conservancy’s proposition for a unified UNESCO World Heritage Site frames the Florida Big Bend as a single, interconnected cultural landscape and natural system of outstanding value that merits international recognition and long-term protection. The Big Bend Coastal Conservancy is a nonprofit established 15 years ago to advocate for the preservation of natural locations in a six-county region from the tip of Cape San Blas in Gulf County to the Suwannee River. This area includes the coastal counties of Dixie, Franklin, Gulf, Jefferson, Taylor and Wakulla counties.

The core argument for designating the Big Bend as a World Heritage Site includes its unusually intact mosaic of barrier islands, salt marshes, seagrass beds, estuaries, freshwater springs and rivers, and associated cultural places and traditions. These places demonstrate superlative ecological processes, exceptional biodiversity and a deep historical record of human interaction with a sensitive coastal environment. The proposition emphasizes landscape-level integrity and the rarity — within the continental U.S. — of such large, continuous, low-development coastal ecosystems.

Natural values: The proposition highlights the Big Bend’s living coastal systems — extensive seagrass meadows, estuarine nurseries, migratory bird corridors, rare tidal marsh types, freshwater karst springs and undammed rivers such as portions of the Apalachicola watershed — as key reasons for inscription. It argues these systems sustain regionally important fisheries, support threatened and endemic species, and preserve intact ecological processes (hydrology, sediment transport, nutrient cycling) that are increasingly rare globally. Seagrass and marsh resilience, large undeveloped barrier islands and the connectivity between upland, riverine and marine habitats form the biological and geomorphic backbone of the nomination.

Cultural and historic values: Interwoven with the natural story is a strong cultural-heritage case: prehistoric and historic archaeological sites, Indigenous and early colonial landscapes (including Spanish mission-era sites and forts), historic fisheries and maritime traditions, and small coastal communities whose economies and cultural practices are shaped by the estuarine environment. The proposition positions these elements as integral parts of a cultural landscape in which human livelihoods and beliefs evolved alongside, and adapted to, the Big Bend’s natural rhythms. This combined cultural-natural argument aims to qualify the property as a mixed (cultural and natural) World Heritage nomination.

Serial and zoned approach: Practically, the proposition recommends a serial, multi-component nomination under a single management framework, stitching together federally and state-managed parks, preserves, seagrass and estuarine preserves, significant archaeological sites and community landscapes. Such a zoned approach (core protected areas and buffer and cooperation zones) is presented as the optimal way to respect existing land ownership while demonstrating the site’s overall integrity and continuity. The document stresses interoperable management plans, shared monitoring protocols and joint governance mechanisms involving local counties, state agencies, nongovernmental organizations and tribal stakeholders.

Threats, benefits and management: The proposal proposition clearly lists threats — sea-level rise and coastal inundation, altered freshwater flows and upstream water management, pollution and harmful algal blooms, development pressure and climate impacts on key habitats — and ties inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage Site list to tangible conservation benefits. Those benefits include improved statutory and funding leverage, coordinated restoration and research programs, sustainable tourism pathways and stronger community stewardship. The management strategy couples scientific monitoring with community education and an economic plan that aims to align local livelihoods with conservation outcomes.

Next steps and justification: Finally, the proposition maps next steps (formal state/federal endorsement, placement on the U.S. Tentative List, preparation of a nomination dossier and stakeholder consultation). The combined natural processes, biodiversity and living cultural landscape meet multiple World Heritage criteria. UNESCO inscription isn’t the endpoint but would be a durable instrument for landscape-scale conservation, climate adaptation and cultural continuity for Florida’s Big Bend region.

Overall, the Big Bend Coastal Conservancy’s proposition integrates local conservation priorities within an international protection model to protect ecological connectivity, cultural heritage and community resilience across the Florida Big Bend.

Capt. Tony Murray is founder and director of the Big Bend Coastal Conservancy. James Dunbar, Ph.D., is chair of the Aucilla Research Institute. Madeleine Hirsiger Carr, Ph.D., is an independent scholar with a focus on U.S. cultural history. Banner photo: St. Marks Lighthouse, located in Wakulla County in St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge (iStock image).

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. To support The Invading Sea, click here to make a donation. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at nc*****@*au.edu.