By Steve Rintoul, CSIRO; Esmee van Wijk, CSIRO; Laura Herraiz Borreguero, CSIRO; and Madelaine Gamble Rosevear, University of Tasmania

Sometimes, we get lucky in science. In this case, an oceanographic float we deployed to do one job ended up drifting away and doing something else entirely.

Equipped with temperature and salinity sensors, our Argo ocean float was supposed to be surveying the ocean around the Totten Glacier, in eastern Antarctica. To our initial disappointment, it rapidly drifted away from this region. But it soon reappeared further west, near ice shelves where no ocean measurements had ever been made.

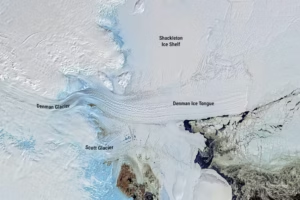

Drifting in remote and wild seas for two-and-a-half years, the float spent about nine months beneath the massive Denman and Shackleton ice shelves. It survived to send back new data from parts of the ocean that are usually difficult to sample.

Measurements of the ocean beneath ice shelves are crucial to determine how much, and how quickly, Antarctica will contribute to sea-level rise.

What are Argo ocean floats?

Argo floats are free-floating robotic oceanographic instruments. As they drift, they rise and fall through the ocean to depths of up to 2 kilometers, collecting profiles of temperature and salinity. Every ten days or so they rise to the surface to transmit data to satellites.

These floats have become a mainstay of our global ocean observing system. Given that 90% of the extra heat stored by the planet over the past 50 years is found in the ocean, these measurements provide the best thermometer we have to track Earth’s warming.

Little buoy lost

We deployed the float to measure how much ocean heat was reaching the rapidly changing Totten Glacier, which holds a volume of ice equivalent to 3.5 metres of global sea-level rise. Our previous work had shown enough warm water was reaching the base of the ice shelf to drive the rapid melting.

To our disappointment, the float soon drifted away from Totten. But it reappeared near another ice shelf also currently losing ice mass and potentially at risk of melting further: the Denman Glacier. This holds ice equivalent to 1.5m of global sea-level rise.

The configuration of the Denman Glacier means it could be potentially unstable. But its vulnerability was difficult to assess because few ocean measurements had been made. The data from the float showed that, like Totten Glacier, warm water could reach the cavity beneath the Denman ice shelf.

Our float then disappeared under ice and we feared the worst. But nine months later it surfaced again, having spent that time drifting in the freezing ocean beneath the Denman and Shackleton ice shelves. And it had collected data from places never measured before.

Why measure under ice?

As glaciers flow from the Antarctic continent to the sea, they start to float and form ice shelves. These shelves act like buttresses, resisting the flow of ice from Antarctica to the ocean. But if the giant ice shelves weaken or collapse, more grounded ice flows into the ocean. This causes sea level to rise.

What controls the fate of the Antarctic ice sheet – and therefore the rate of sea-level rise – is how much ocean heat reaches the base of the floating ice shelves. But the processes that cause melting in ice-shelf cavities are very challenging to observe.

Ice shelves can be hundreds or thousands of meters thick. We can drill a hole through the ice and lower oceanographic sensors. But this is expensive and rarely done, so few measurements have been made in ice-shelf cavities.

What the float found

During its nine-month drift beneath the ice shelves, the float collected profiles of temperature and salinity from the seafloor to the base of the shelf every five days. This is the first line of oceanographic measurements beneath an ice shelf in East Antarctica.

There was only one problem: because the float was unable to surface and communicate with the satellite for a GPS fix, we didn’t know where the measurements were made. However, it returned data that provided an important clue. Each time it bumped its head on the ice, we got a measurement of the depth of the ice shelf base. We could compare the float data to satellite measurements to work out the likely path of the float beneath the ice.

These measurements showed the Shackleton ice shelf (the most northerly in East Antarctica) is, for now, not exposed to warm water capable of melting it from below, and therefore less vulnerable.

However, the Denman Glacier is exposed to warm water flowing in beneath the ice shelf and causing the ice to melt. The float showed the Denman is delicately poised: a small increase in the thickness of the layer of warm water would cause even greater melting.

What does this mean?

These new observations confirm the two most significant glaciers (Denman and Totten) draining ice from this part of East Antarctica are both vulnerable to melt caused by warm water reaching the base of the ice shelves.

Between them, these two glaciers hold a huge volume of ice, equivalent to five meters of global sea-level rise. The West Antarctic ice sheet is at greater risk of imminent melting, but East Antarctica holds a much larger volume of ice. This means the loss of ice from East Antarctica is crucial to estimating sea-level rise.

Both the Denman and Totten glaciers are stabilized in their present position by the slope of the bedrock on which they sit. But if the ice retreated further, they would be in an unstable configuration where further melt was irreversible. Once this process of unstable retreat begins, we are committed. It may take centuries for the full sea-level rise to be realized, but there’s no going back.

In the future, we need an array of floats spanning the entire Antarctic continental shelf to transform our understanding of how ice shelves react to changes in the ocean. This would give us greater certainty in estimating future sea-level rise.![]()

Steve Rintoul is a CSIRO fellow; Esmee van Wijk is a senior scientist at CSIRO; Laura Herraiz Borreguero is a physical oceanographer at CSIRO; and Madelaine Gamble Rosevear is a postdoctoral fellow in physical oceanography at the University of Tasmania.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. Banner photo: Another image of a glacier (Pete Harmsen, CC BY-ND).

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. To support The Invading Sea, click here to make a donation. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe.

We could have sea level risen off fifty feet eventually.