By Robert C. Jones Jr., University of Miami News

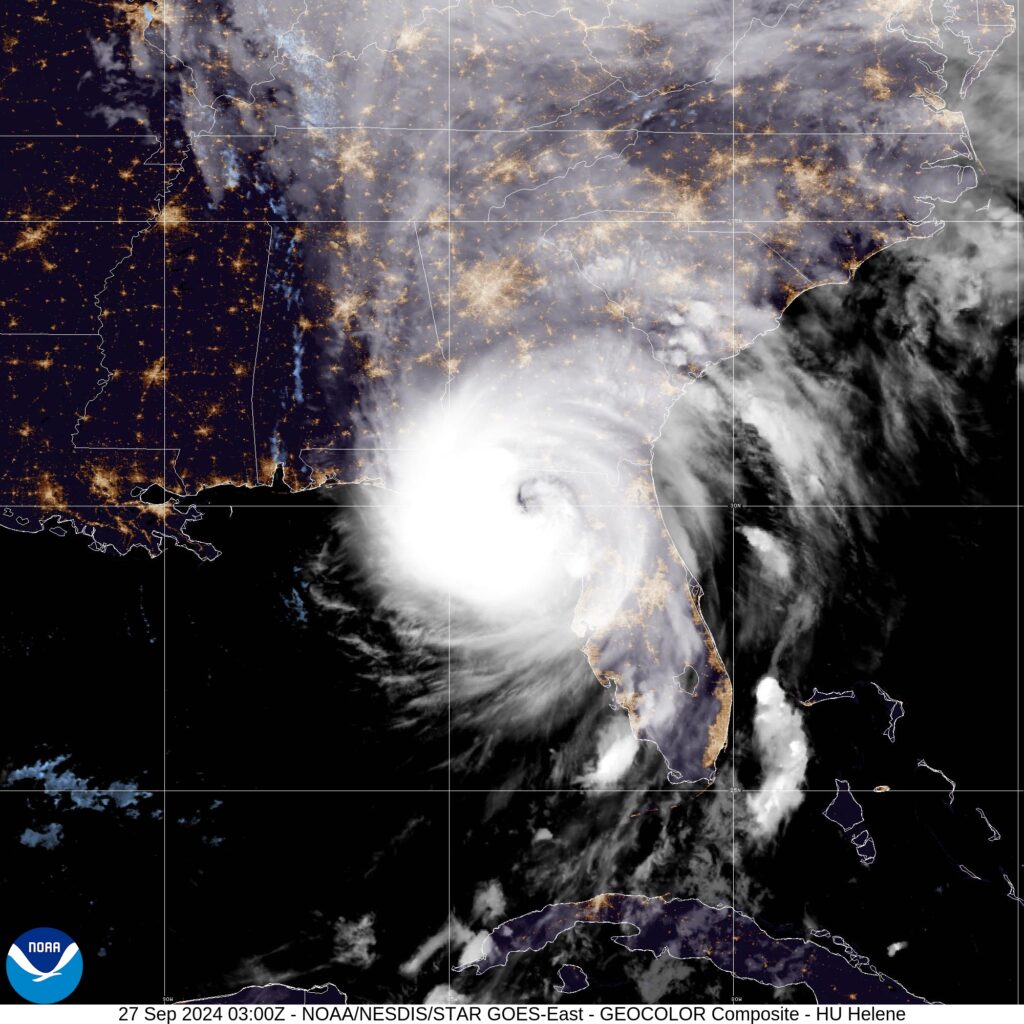

Sharon Austin wept. Flood waters from Hurricane Helene’s nearly seven-foot-high storm surge had overwhelmed her villa on Longboat Key, Florida, last September, making her lodgings unlivable.

When she walked into the two-bedroom unit two days after the storm had passed, the emotions she experienced from seeing her waterlogged floors, furniture and walls got the best of her. “I just broke down and cried,” she recalled.

Only days later, another cyclone, Milton, would also come impact the 10-mile-long barrier island on the state’s southwest coast, adding to Austin’s misery. But despite the double whammy, she rebuilt and moved back into her refurbished digs just before the year ended.

Now, as the 2025 Atlantic hurricane season looms, Austin views what could happen in the months ahead with trepidation. “I got a little PTSD from last year,” she admits. “So, I’m a little apprehensive, a little nervous, a little unsure.”

Her fears are warranted. Forecasters with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) are predicting a 60% chance of an above-normal Atlantic hurricane season, which runs June 1 to Nov. 30. Their outlook calls for 13 to 19 named storms, with six to 10 becoming hurricanes and three to five reaching major status (winds of 111 miles per hour or higher).

A confluence of factors — including the neutral phase of the tropical Pacific climate pattern known as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation or ENSO, warmer than average ocean temperatures and the absence of high wind shear that weakens storms — “likely means that forecast will be accurate, that another unusually busy season awaits,” said Ben Kirtman, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science.

Ocean temperatures

NOAA’s forecast for an above-normal season comes even as Atlantic ocean temperatures, a key factor in hurricane formation and intensity, are cooler than they have been in previous years.

“They’re cooler, yes,” Kirtman said. “But they’re still warmer than normal, just not as crazy warm as they were last year or the year before.”

Brian McNoldy, a senior research associate and tropical cyclone expert at the Rosenstiel School, concurred. “Much of the tropical and subtropical Atlantic is cooler than it was at this time a year ago,” he said. “If we look at the sea surface temperature averaged across the main development region (MDR), it is just slightly above average for the date. Then, if we look at the ocean heat content averaged across the MDR, it is below where it was in 2024 and 2023 for the date, but higher than every other year. And ocean heat content tells us more about the available energy in the upper layers of the ocean, not just at the surface.”

The decay of El Niño, ENSO’s warm phase (La Niña represents the cool phase) could be the reason for cooler temperatures in the Atlantic, McNoldy suspects. “Since hurricanes are fueled by warm water, and the tropical Atlantic is only slightly warmer than average, we might simply project slightly above-average (hurricane) activity if that anomaly persists for another three to five months,” he said.

A season of uncertainty

As such, the 2025 Atlantic hurricane season will be one filled with some degree of uncertainty as it evolves, with the duration of ENSO’s neutral phase being one of the primary climate patterns forecasters will be watching.

“The outlook for the peak months of hurricane season (August, September and October) is about 55% probability of it remaining in the neutral phase,” McNoldy said. “All other things being equal, the La Niña phase tends to enhance Atlantic hurricane activity while the El Niño phase tends to suppress activity. So, not surprisingly, the neutral phase means no strong forces one way or the other.”

Then, there is the role that the weather phenomenon known as the Madden-Julian Oscillation, or MJO, will play. An eastward moving disturbance of clouds, rainfall, winds and pressure, the MJO traverses the planet in the tropics and returns to its initial starting point on the order of 30 to 60 days.

“When it’s in its active phase and propagates into the Atlantic, that could light up the hurricane season, and when it propagates in its suppressed phase, that’ll tend to suppress hurricanes,” said Kirtman, who is also the William R. Middelthon III Endowed Chair of Earth Sciences. “And, of course, the second factor that’s important on those sub-seasonal timescales is the dust. If we have a big dust outbreak, that’ll suppress storms. But we won’t know about those factors until we get more into the heart of the season.”

Will the trend of increased hurricane activity along the Gulf Coast continue? Last year, for example, that region bore the brunt of the season’s most powerful storms, with Beryl, Debby, Francine, Helene and Milton all making landfall along that coastline.

Ocean temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico continue to be alarmingly high, providing the fuel storms need to develop and rapidly intensify. “Last year, the Gulf ocean heat content was higher by about 30 kilojoules per square centimeter compared to the previous 10 years, and that’s a big number,” said Lynn “Nick” Shay, a professor of oceanography in the Rosenstiel School’s Department of Ocean Sciences. “That’s 15 to 20% of what the maximums usually are. And we saw what the manifestation of that was last year with Helene, Milton and the other storms. It can explain why we’re getting more intense storms because there’s more heat available for them.”

Shay, who investigates warm water eddies that break off from the Loop Current in the Gulf and supercharge hurricanes, will deploy a suite of six additional ElectroMagnetic Autonomous Profiling Explorer, or EM-APEX, floats from Hurricane Hunter aircraft out of the 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron at Keesler Air Force Base in Biloxi, Mississippi, to monitor the heat content in the eastern and central Gulf.

“These floats will make two profiles a day for the next 180 days encompassing the hurricane season,” Shay said. “The temperature, salinity and current profiles will help us not only sort out heat but also the current that moves around the heat.”

Shay isn’t the only researcher who’ll be busy this hurricane season. Andy Hazelton, an associate scientist at the Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies, or CIMAS, who has been fascinated by hurricanes ever since he was a little boy and has flown on several NOAA Hurricane Hunter aircraft missions, is part of a modeling team that includes CIMAS colleagues Bill Ramstrom and Lewis Gramer that will subject the Hurricane Analysis and Forecast System (HAFS) to a new round of testing.

Technology called storm-following nests make the high-resolution forecasts from HAFS possible. Much like a magnifying glass, the nest gives National Hurricane Center forecasters a simulated view of a storm’s structure, allowing them to see more accurate details of the storm’s eyewall, clouds, rainbands, wind field and more.

“This season, rather than having a version of the model tracking one hurricane, we’ll employ multiple storm-following nests to produce high-definition forecasts for several hurricanes simultaneously,” Hazelton said.

Meanwhile, Sharan Majumdar, a professor of atmospheric sciences, and his research group are studying African easterly waves from which some of the most powerful hurricanes can develop. He is investigating the performance of the new Artificial Intelligence Forecasting System (AIFS) developed by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts in predicting the formation of tropical cyclones from these waves and how AIFS compares with the centre’s regular physics-based model. Majumdar will also visit the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, to learn about the Model for Prediction Across Scales, which will be used in his new project supported by the National Science Foundation.

This piece was originally published at https://news.miami.edu/stories/2025/05/active-hurricane-season-looms.html. Banner photo: Hurricane Milton from the International Space Station (NASA/Michael Barratt, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons).

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. To support The Invading Sea, click here to make a donation. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at nc*****@*au.edu.