By Ivis García and Shannon Van Zandt, Texas A&M University

When powerful storms hit your city, which neighborhoods are most likely to flood? In many cities, they’re typically low-income areas. They may have poor drainage, or they lack protections such as seawalls.

New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward, where hundreds of people died when Hurricane Katrina broke a levee in 2005, and Houston’s Kashmere Gardens, flooded by Hurricane Harvey in 2017, are just two among many examples.

With those disasters in mind, the Federal Emergency Management Agency made a big change to its Local Mitigation Planning Policy Guide in 2023. The agency began encouraging cities, towns and counties to address equity in their hazard mitigation plans, which outline how they will reduce disaster risk.

Local governments have an incentive to follow those federal guidelines: Those that want to receive FEMA hazard mitigation assistance – money which can be used to repair aging infrastructure like roads, bridges and flood barriers – or funding from other programs such as dam rehabilitation have to develop local mitigation plans and update them every five years.

The new guidance required cities to both consider social vulnerability among neighborhoods in their disaster mitigation planning and involve socially vulnerable communities in those discussions in ways they hadn’t before.

However, as the U.S. heads into what forecasters predict will be an active 2025 hurricane season, June 1 through Nov. 30, that guidance has changed again. The Trump administration’s new FEMA Local Mitigation Planning Policy Guide 2025 talks about public involvement in planning but strips any mention of equity, income or social vulnerability. It mentions using “projections for the future” to plan but removes references to climate change.

Who is most at risk in hurricanes, and why

Hurricanes and other storms that cause flooding don’t affect everyone in the same way.

A legacy of redlining and discrimination in many U.S. cities left poor and minority families living in often risky areas. These neighborhoods also tend to have poorer infrastructure.

In the past, local mitigation plans just focused on fixing roads or protecting property in general from storm damage, without recognizing that socially vulnerable groups, such as low-income or elderly populations, were more likely to be hardest hit and take much longer to recover.

The FEMA 2023 guidance encouraged communities to consider both the highest risks and which neighborhoods would be least able to respond in a disaster and address their needs.

The equity requirement was designed to ensure that local plans didn’t just protect those with the most wealth or political influence but considered who needs the help most. That might mean providing information in multiple languages in emergency alerts or investing in flood prevention in neighborhoods with aging infrastructure like roads, bridges and flood barriers.

How New York City’s 2024 plan helped

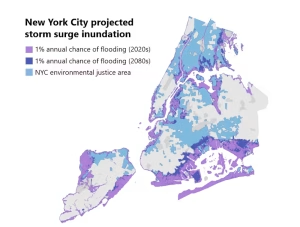

New York City’s 2024 Hazard Mitigation Plan, for example, included a thorough social vulnerability assessment to identify neighborhoods with high percentages of people who were living in poverty or were older, disabled or weren’t fluent in English.

Knowing where disaster risk and social vulnerability overlapped allowed the city to boost investments in flood protection, emergency communication and cooling centers during summer heat in neighborhoods such as the South Bronx and East Harlem. These neighborhoods historically faced some of the greatest risks from disasters but saw little investment.

Further, New York’s plan calls for expanding outreach and early warning systems in multiple languages and enhancing infrastructure in areas with high concentrations of Spanish speakers. These kinds of changes help ensure that vulnerable residents are more likely to be better protected when disaster strikes.

Why is FEMA dropping that emphasis now?

FEMA’s reasoning for the guidance change in 2025: make it quicker and easier to get plans approved and unlock federal funding for projects like flood barriers, storm shelters and buyouts in areas at high risk of damage.

It’s a pragmatic move, but one that raises big questions about whether residents who are least able to help themselves will be overlooked again when the next disaster strikes.

And FEMA isn’t alone — other agencies, like the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and its Community Development Block Grant – Disaster Recovery program, have made similar changes to their own disaster planning rules. Community Development Block Grant funds for disaster recovery are flexible and can be used for things like rebuilding homes and businesses, restoring infrastructure and helping local economies recover.

What this means for low-income areas

Some experts worry that the changes might mean low-income and other at-risk communities will be ignored again when cities develop their next five-year mitigation plans. Research from the Government Accountability Office shows that when something is required by law, it gets done. When it’s just a suggestion, it’s easy to skip, especially in places with fewer resources or less political will to help.

But the short-lived rules may have already helped in one important way: They made cities and states pay attention to social vulnerability, climate change and the needs of all their residents.

Many local leaders have learned the value of using data to understand where socially vulnerable residents face high disaster risks. And they have a model now for involving communities in decision-making. Even if those steps are no longer required, the hope is that these good habits will stick.

Where and how communities invest in disaster protection affects who stays safe and who faces higher risks from flooding, hurricanes and other disasters. When government policy shifts, it’s not just about paperwork – it’s about real people.![]()

Ivis García is an associate professor of landscape architecture and urban planning and Shannon Van Zandt is a professor of landscape architecture and urban planning, both at Texas A&M University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. Banner photo: Houses affected by flooding from Hurricane Harvey in Orange, Texas, in 2017 (U.S. Army photo by Staff Sgt. Carl Greenwell, via Defense Visual Information Distribution Service).

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. To support The Invading Sea, click here to make a donation. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at nc*****@*au.edu.