By Diana Udel, University of Miami News

Marine heatwaves are reshaping ocean food webs in ways that slow the transport of carbon to the deep sea, according to new research. By disrupting the ocean’s “biological carbon pump,” these extreme warming events may weaken one of Earth’s key natural processes for moving carbon from the surface into the deep ocean.

The study, published on Oct. 6 in the journal Nature Communications, was led by Mariana Bif, an assistant professor in the Department of Ocean Sciences at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science, and previously a research specialist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI). The work was led by Bif in collaboration with scientists from MBARI, the Hakai Institute, Xiamen University, the University of British Columbia, the University of Southern Denmark, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

“The ocean has a biological carbon pump, which normally acts like a conveyor belt carrying carbon from the surface to the deep ocean,” said Bif. “Our study shows that these heatwaves disrupted plankton communities at the base of the food web, jamming that conveyor belt and slowing the transport of carbon into the deep ocean where it can be locked away for centuries.”

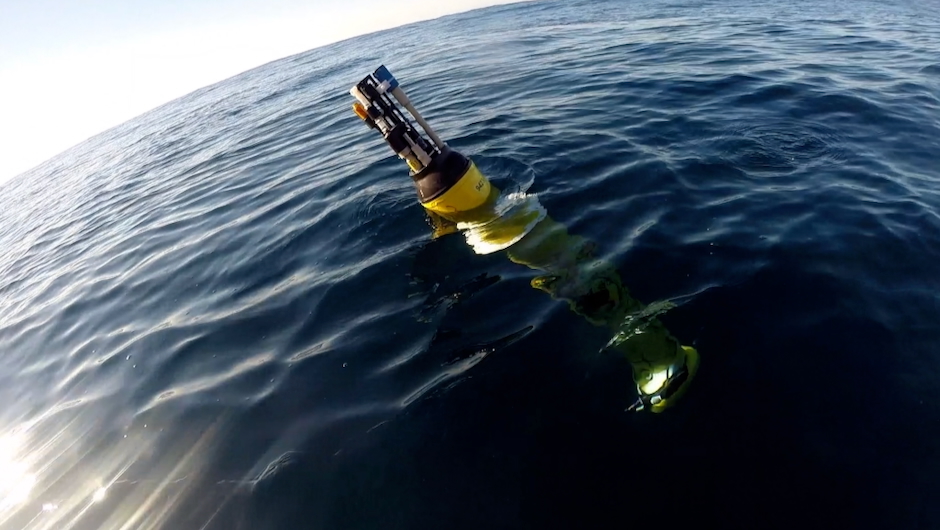

To track the effects of marine heatwaves on plankton and carbon cycling, the team drew on two major sources of long-term ocean observations: robotic floats from the Biogeochemical Argo (BGC-Argo) program and the Global Ocean Biogeochemistry Array, including the Global Ocean Biogeochemistry Array (GO-BGC), a U.S. National Science Foundation-funded project led by MBARI, and one of the oldest ship-based time series monitoring programs, Line P, operated by Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

By combining float data on ocean chemistry and biology with genetic and pigment analyses of plankton, the researchers traced how shifts in the food web influenced carbon flows to the deep ocean, where it can remain stored for thousands of years.

The analysis focused on two major Northeast Pacific heatwaves:

During the 2013–2015 heatwave, surface carbon production by photosynthetic plankton was high in the second year, but rather than sinking rapidly to the deep sea, small carbon particles accumulated around 200 meters (roughly 660 feet) below the surface.

During the 2019–2020 heatwave, record-high carbon particle buildup was observed at the surface during the first year. This accumulation could not be explained by plankton production alone but was likely caused by the recycling of carbon by marine life and the buildup of detrital waste. That carbon pulse later sank to the twilight zone, where it lingered at depths between 200 and 400 meters (roughly 660–1,320 feet) instead of descending to the deep sea.

The team attributed these differences in carbon transport between the two heatwaves to shifts in phytoplankton populations that cascaded through the food web. A rise in smaller grazers — organisms that produce slower-sinking waste particles — meant that more carbon was retained and recycled near the surface and upper twilight zone rather than transported to deeper waters.

Although both heatwaves disrupted carbon transport, they did so in distinct ways. In one case, enhanced plankton production led to carbon buildup in the twilight zone; in the other, surface debris and recycled carbon sank only partway before stalling. In both scenarios, carbon was more likely to return to the atmosphere rather than be stored long-term in the deep ocean.

“Our results show that not all marine heatwaves are the same. Different plankton lineages respond in different ways, with cascading impacts on how the ocean moves and stores carbon,” Bif said. “This underscores why long-term, coordinated monitoring of the ocean is so critical.”

Marine heatwaves are becoming more frequent and intense as the planet warms, threatening fisheries, marine ecosystems and the climate system itself. By disrupting the delicate balance of ocean food webs, these events may reduce the ocean’s ability to absorb carbon dioxide.

“This research marks an exciting new chapter in ocean monitoring,” said coauthor Ken Johnson, MBARI senior scientist and lead principal investigator for the NSF-Funded Global Ocean Biogeochemistry Array project. “Robotic floats, pigment chemistry and genetic sequencing each told part of the story. Together, they provided a rare before-during-after view of how extreme events reshape ocean processes.”

The study titled “Marine heatwaves modulate food webs and carbon transport processes” was published Oct. 6 in the journal Nature Communications. The authors are Mariana B. Bif, MBARI and University of Miami Rosenstiel School, Colleen T.E. Kellogg, Hakai Institute, Yibin Huang, Xiamen University, Julia Anstett, University of British Columbia, Sachia Traving, University of Southern Denmark, M. Angelica Peña, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Steven J. Hallam, University of British Columbia and Kenneth S. Johnson, MBARI.

This piece was adapted from a MBARI press release and originally published at https://news.miami.edu/rosenstiel/stories/2025/10/marine-heatwaves-disrtrupt-ocean-food-webs-and-slow-carbon-transport-to-the-deep-sea.html. Banner photo: The sun rises over the Atlantic Ocean (iStock image).

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. To support The Invading Sea, click here to make a donation. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at nc*****@*au.edu.