By Carrie Stevenson, UF/IFAS

As the name implies, they are haunting — long stretches of standing, dead trees with exposed roots. These “ghost forests” are an unsettling scene in unsettling times for the environment. While coastal erosion is a fact of life — caused by incoming waves, hurricanes and longshore drift of beach sand — the rate of its occurrence is startling lately.

Global rises in sea level due to increased atmospheric carbon levels mean more saltwater is moving into flat, coastal habitats that once served as a buffer from the open water. Salt is an exceedingly difficult compound for plants to handle, and only a few species have evolved mechanisms for tolerating it.

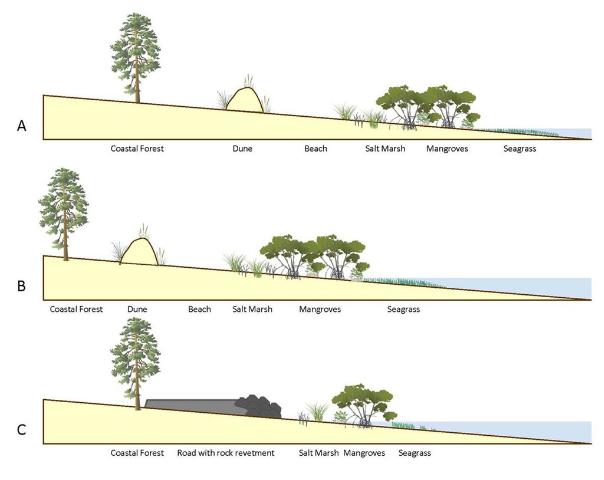

Low-growing salt marshes or thick mangrove stands have always served as “first line of defense” buffers to take in wave action and absorb saltwater. If shorelines have too much wave action for marshes to form, wide stretches of sandy beach and dunes serve the same function, protecting the inland species of shrubs and trees.

Many coastal areas are flat and stay at or just above sea level for thousands of yards, or even miles. This means that even a small increase in sea level can send saltwater deep into previously freshwater systems, drowning the marsh and flooding stands of oak and pine.

The salt and sulfate in seawater will kill a tree quickly, although it may remain standing, dead, for months or years. Hurricanes and tropical storms exacerbate that damage, scouring out chunks of shoreline and knocking down already-unstable trees.

A slow increase in sea level could be tolerated and adapted to as salt marshes move inland and replace non-salt tolerant species. But this process of ecological succession can be interrupted if erosion and increased water levels occur too quickly. And if there is hard infrastructure inland of the marshes (like roads or buildings), the system experiences “coastal squeeze,” winnowing the marsh to a thin, eventually nonexistent ribbon, with no natural protection for that expensive infrastructure.

Ghost forests are popping up everywhere. Popular Mechanics magazine reported on a study in 2021 that used satellite imagery to document how 11% of a previously healthy forest was converted to standing dead trees along the coast of North Carolina.

The trees died within a span of just 35 years (1984-2019). During that time frame, this stretch of coastline also experienced an extended drought and Category 3 Hurricane Irene. These impacts sped up the habitat loss, with over 19,000 hectares converted from forest to marsh and 1,100 hectares of marsh vegetation gone, becoming open water.

Due to increased coastal flooding and saltwater standing in forested areas, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service employees are concerned that the historic Harriett Tubman Byway in Maryland — part of the famed underground railroad of the Civil War era — will soon be gone. Over 5,000 acres of tidal marsh have converted to open water in the area and large stands of trees have died.

In Escambia County, trees along Escambia and Blackwater Bay are dying due to salt damage and heavy erosion. Hurricane Sally delivered a knockout punch to many remaining trees along the scenic bluffs of the bay.

Sea level has risen over 10” in the past 100 years in the Pensacola Bay area, and even mid-range Army Corps of Engineers estimates expect 0.6 to 1.4 feet of rise in the area by 2045. There are some actions we can take to mitigate future damage, including preserving buffer areas along shorelines that allow coastal plants to retreat. Building a “living shoreline” of vegetation along a piece of waterfront property instead of using a seawall can help, especially if the vegetation growth outpaces sea level rise.

Carrie Stevenson is the Coastal Sustainability Agent for the UF/IFAS Escambia County Extension Office, and has been with the organization since 2003. An earlier version of this piece first appeared at https://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/escambiaco/2021/04/28/weekly-what-is-it-ghost-forests/

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu.