By Kaitlin Sullivan for Energy Innovation Policy and Technology LLC

In 2023, hospitals in Florida, Brooklyn and Los Angeles shut down. Some evacuated patients in preparation for hurricanes feeding off of warming coastal waters, others were forced to close after historic rainfall cut power to a city of nearly four million people. On the other side of the globe, floods and landslides shuttered 12 health care facilities in five provinces in southern Thailand.

Which is why in December 2023, delegates from all 199 countries of the United Nations met in Dubai to attend the first-ever Health Day at a Conference of Parties (COP) summit. The COP28 meeting highlighted the fact that the climate crisis is also a health crisis.

Health care systems around the world are already being strained by natural disasters and heat waves, something experts predict will worsen in the coming decades.

For example, Pakistan’s devastating floods in 2022 impacted an estimated 1,460-plus health care facilities, about 10% of the country’s total. The following weeks saw outbreaks of both water-borne and vector-borne infectious diseases, adding to the burden thrust upon the already weakened health care system.

Summer 2023 was also the hottest on record, marked by deadly heat waves and wildfires that tore through forests, seas and cities.

“The Northern Hemisphere just had a summer of extremes — with repeated heat waves fueling devastating wildfires, harming health, disrupting daily lives and wreaking a lasting toll on the environment,” World Meteorological Organization Secretary-General Petteri Taalas said in a statement.

In Arizona, the extreme heat put pressure on power grids and spurred an influx of people in need of medical care for heat stress. Heat-related emergency room visits rose by 50% on days that reached a wet-bulb temperature of at least 89.6 degrees Fahrenheit, a 2021 Taiwanese study found. Simply put, wet-bulb temperatures take into account both heat and humidity, which makes it more difficult for sweat to evaporate and therefore harder for people to cool themselves.

Over the past five years, the number of heatstroke patients admitted to hospitals in Pakistan during the summer months increased around 20% annually, the medical director of a Pakistani hospital told The Washington Post. In that time, Pakistan endured three of its five hottest summers.

The recent hospital closures in Pakistan, Thailand and the United States are representative of a larger trend that’s already in motion. According to the World Health Organization, 3.6 billion people already live in areas highly susceptible to climate change. A recent paper led by Renee Salas, published in Nature Medicine, used the United States, a country with one of the most robust health systems in the world, to illustrate how climate change will impact both the number of people needing medical care as well as hospitals’ ability to carry out that care.

From 2011 to 2016, floods, storms and hurricanes caused over $1 billion in damages across the U.S. Using Medicare data from that timeframe, Salas and colleagues found that in the week following an extreme weather event, emergency room visits and deaths rose between 1.2% and 1.4%, and deaths remained elevated for six weeks following the event.

The researchers also found that mortality rates were two to four times higher in counties that experienced the greatest economic losses following a disaster. Moreover, these counties also had higher emergency department use, highlighting how damage to infrastructure, such as power outages and thwarted transportation, can compound the toll climate change takes on human health.

Future threats

Between 2030 and 2050, climate change-driven malnutrition, malaria, diarrhea and heat stress are expected to cause 250,000 additional deaths per year. And climate change is expected to worsen more than half of known human pathogenic diseases, expanding the range of fungal infections and increasing the risk of viral pathogens and mosquito-borne diseases.

At the same time, health care infrastructure will face increasing strain from the impacts of extreme weather –– power outages, flooding, damage to buildings –– as well as from the mounting health issues, infections and diseases exacerbated by climate change.

A December 2023 report published by XDI (Cross Dependency Initiative), an Australian climate risk data company, estimated that by the end of this century, one in 12 hospitals worldwide could be at risk of total or partial shutdown due to extreme weather.

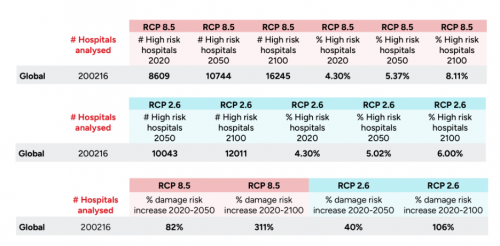

The researchers used two versions of the Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) to compare the projected risks to hospital infrastructure in two different scenarios of a global temperature rise of about 1.8˚C vs. 4.3˚C by the year 2100. The researchers also examined the increase in climate risk to 200,216 hospitals around the globe from flooding, fires and cyclones. At worst, fires can completely destroy buildings, but they also create dangerous levels of air pollution and smoke that can land more patients in the hospital and strain those already being treated. Flooding and cyclones can render hospitals unusable.

In both low- and high-emissions scenarios, a significant number of the study hospitals would be at high risk of total or partial shutdown by 2100: 12,011 (6%) in the lower emissions scenario, compared to 16,245 (8%) hospitals in the high-emissions scenario. Under the worst case scenario, 10,744 hospitals –– more than 5% of those included in the analysis –– would already be high risk by 2050. The lower risk scenario doesn’t project a much better outcome, estimating that 10,043 hospitals would still be high risk in 2050.

Human-driven climate change has already increased damage to hospitals by 41% between 1990 and 2020. Nowhere is this phenomenon more prevalent than in Southeast Asia, which has seen a 67% increase in risk of damage since 1990. On this trajectory, one in five hospitals in Southeast Asia would be at high risk for climate-driven damage by the end of the century. More than 70% of these hospitals would be in low-to-middle-income nations.

The XDI report estimated more than 5,800 hospitals in South Asia, an area that includes India, the world’s most populous country, would be at high risk for shutting down under the 4.3˚C increase scenario. More than half of hospitals in the Central African Republic and more than one-quarter of hospitals in the Philippines and Nepal would face the same fate.

Contrary to popular belief, high-income nations are also not immune. The model projected that North America would experience the biggest increase in risk of weather-driven damage to hospital infrastructure by 2100, with a more than five-fold increase compared to 2020.

If world leaders can limit warming to 1.8˚C and rapidly phase out fossil fuels starting now, the data suggests the risk of damage to hospitals would be cut in half by the end of the century compared to the high-emissions scenario.

How hospitals can prepare

Hospitals need to brace for a future with more demand for care and a higher risk of infrastructure being damaged by extreme weather.

In a February 2024 review published in International Journal of Health Planning and Management, Yvonne Zurynski led a team of researchers that used data from 60 studies published in 2022 and 2023 to identify ways in which the health care system can build resilience in the midst of a changing climate. Forty-four of the studies reviewed focused on the strains climate change puts on health care workforces, most commonly hospital staff. The same number of studies also reported how hospitals plan to respond to a climate-related event, most commonly hurricanes, followed by floods and wildfires. The plans included how hospitals could minimize staff burnout and safely evacuate patients if needed.

The team found six key ways hospitals and health workers can adapt to the health system impacts of climate change: training/skill development, workforce capacity planning, interdisciplinary collaboration, role flexibility, role incentivization and psychological support.

For training and skills development, the studies agreed that all health care workers should be trained to recognize and treat climate-specific health conditions, including wildfire smoke exposure, heat stroke and water-borne diseases.

Infrastructure must be designed to be more climate resilient. Many facilities are susceptible to power outages or are not equipped to cope with wildfire smoke or the loss of running water. Being prepared also includes training staff in techniques to evacuate patients from hospitals that can no longer run due to a climate change-fueled extreme weather event.

Health care systems also need to be flexible and respond to climate-driven health crises as they emerge. This approach encompasses workforce capacity planning, interdisciplinary collaboration and role flexibility. In practice, such an approach may include hiring care staff with multiple specialties, to ensure health care teams can be flexible when unexpected pressures arise.

Health care systems can also incentivize work during high-pressure events. This strategy could take a physical form, such as compensating staff extra for working during a climate response. It could also be intrinsic. Staff may feel it is their duty to work during a climate-related disaster, feeling a duty to both their profession and the people they serve, the authors write. Both are examples of role incentivization.

To make this approach sustainable, it is paramount that health systems have a network in place to care for their employees’ mental health. Providing psychological support was a recurring theme in the studies Zurynski and her team reviewed. Hospitals could have mental health professionals on call during or after climate events that put pressure on health systems, or recalculate shifts during a disaster to ensure every employee has adequate time to recuperate. A volunteer or reserve workforce that is pulled into action during or following an extreme weather event or infectious disease outbreak could also alleviate some of the stress on health care workers during these times.

Making significant changes to the way hospitals operate may seem daunting, but facilities can start small in their adaptations and create solutions unique to their needs. An example of this approach can be found in a region already steeply impacted by climate change.

About half of all hospitals in Vietnam do not have a reliable source of water, meaning patients often have to bring their own. Faced with this major obstacle to care, three rural hospitals in Vietnam were chosen for a pilot project to make them more climate resilient, starting with water. Water availability in all three hospitals is already a significant challenge due to droughts, floods and creeping saltwater intrusion.

Despite their water challenges, all three institutions in the pilot found unique ways to guard against existing and growing climate threats through community engagement, installation of rainwater catchment and storage systems, saline filtration and better infrastructure to capture nearby streamflows.

Climate change impacts are already pushing health care systems into higher levels of risk, and that trend will continue. It’s vital that hospital leadership teams begin shaping plans for climate resiliency, both related to infrastructure and personnel, to safeguard health care on a changing planet.

Kaitlin Sullivan is a freelance journalist based in Colorado. She has a master’s in health and science reporting from the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY. This piece was originally published by Energy Innovation Policy and Technology LLC at https://energyinnovation.org/2024/04/29/before-the-next-storm-building-health-care-resilience/

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at ncrabbe@fau.edu.