By Edward Doddridge, University of Tasmania

On her first dedicated scientific voyage to Antarctica in March, the Australian icebreaker RSV Nuyina found the area sea-ice free. Scientists were able to reach places never sampled before.

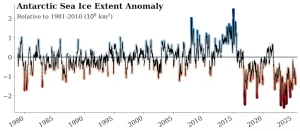

Over the past four summers, Antarctic sea ice extent has hit new lows.

I’m part of a large group of scientists who set out to explore the consequences of summer sea ice loss after the record lows of 2022 and 2023. Together we rounded up the latest publications, then gathered new evidence using satellites, computer modelling and robotic ocean sampling devices. Today we can finally reveal what we found.

It’s bad news on many levels, because Antarctic sea ice is vital for the world’s climate and ecosystems. But we need to get a grip on what’s happening – and use this concerning data to prompt faster action on climate change.

What we did and what we found

We used satellites to understand sea ice loss over summer, measuring everything from ice thickness and extent to the length of time each year when sea ice is absent.

Satellite data was also used to calculate how much of the Antarctic coast was exposed to open ocean waves. We were then able to quantify the relationship between sea ice loss and iceberg calving.

Data from free-drifting ocean robots was used to understand how sea ice loss affects the tiny plants that support the marine food web.

Every other kind of available data was then harnessed to explore the full impact of sea ice changes on ecosystems.

Voyage reports from international colleagues came in handy when studying how sea ice loss affected Antarctic resupply missions.

We also used computer models to simulate the impact of dramatic summer sea ice loss on the ocean.

In summary, our extensive research reveals four key consequences of summer sea ice loss in Antarctica.

1. Ocean warming is compounding

Bright white sea ice reflects about 90% of the incoming energy from sunlight, while the darker ocean absorbs about 90%. So if there’s less summer sea ice, the ocean absorbs much more heat.

This means the ocean surface warms more in an extreme low sea ice year, such as 2016 – when everything changed.

Until recently, the Southern Ocean would reset over winter. If there was a summer with low sea ice cover, the ocean would warm a bit. But over winter, the extra heat would shift into the atmosphere.

That’s not working anymore. We know this from measuring sea surface temperatures, but we have also confirmed this relationship using computer models.

What’s happening instead is when summer sea ice is very low, as in 2016, it triggers ocean warming that persists. It takes about three years for the system to fully recover. But recovery is becoming less and less likely, given warming is building from year to year.

2. More icebergs are forming

Sea ice protects Antarctica’s coast from ocean waves.

On average, about a third of the continent’s coastline is exposed over summer. But this is changing. In 2022 and 2023, more than half of the Antarctic coast was exposed.

Our research shows more icebergs break away from Antarctic ice sheets in years with less sea ice. During an average summer, about 100 icebergs break away. Summers with low sea ice produce about twice as many icebergs.

3. Wildlife squeezed off the ice

Many species of seals and penguins rely on sea ice, especially for breeding and moulting.

Entire colonies of emperor penguins experienced “catastrophic breeding failure” in 2022, when sea ice melted before chicks were ready to go to sea.

After giving birth, crabeater seals need large, stable sea ice platforms for 2–3 weeks until their pups are weaned. The ice provides shelter and protection from predators. Less summer sea-ice cover makes large platforms harder to find.

Many seal and penguin species also take refuge on the sea ice when moulting. These species must avoid the icy water while their new feathers or fur grows, or risk dying of hypothermia.

4. Logistical challenges at the end of the world

Low summer sea ice makes it harder for people working in Antarctica. Shrinking summer sea ice will narrow the time window during which Antarctic bases can be resupplied over the ice. These bases may soon need to be resupplied from different locations, or using more difficult methods such as small boats.

No longer safe

Anarctic sea ice began to change rapidly in 2015 and 2016. Since then it has remained well below the long-term average.

The dataset we use relies on measurements from U.S. Department of Defense satellites. Late last month, the department announced it would no longer provide this data to the scientific community. While this has since been delayed to July 31, significant uncertainty remains.

One of the biggest challenges in climate science is gathering and maintaining consistent long-term datasets. Without these, we don’t accurately know how much our climate is changing. Observing the entire Earth is hard enough when we all work together. It’s going to be almost impossible if we don’t share our data.

Recent low sea ice summers present a scientific challenge. The system is currently changing faster than our scientific community can study it.

But vanishing sea ice also presents a challenge to society. The only way to prevent even more drastic changes in the future is to rapidly transition away from fossil fuels and reach net zero emissions.![]()

Edward Doddridge is a senior research associate in physical oceanography at the University of Tasmania.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. Banner photo: An icebreaker approaches Denman Glacier in March, when there was 70% less Antarctic sea ice than usual (Pete Harmsen, AAD).

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. To support The Invading Sea, click here to make a donation. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe at nc*****@*au.edu.