By Jonathan Levy, Boston University; Howard Frumkin, University of Washington; Jonathan Patz, University of Wisconsin-Madison; and Vijay Limaye, University of Wisconsin-Madison

The Trump administration took a major step in its efforts to unravel America’s climate policies on Thurdsday, when it moved to rescind the 2009 endangerment finding – a formal determination that six greenhouse gases that drive climate change, including carbon dioxide and methane from burning fossil fuels, endanger public health and welfare.

But the administration’s arguments in dismissing the health risks of climate change are not only factually wrong, they’re deeply dangerous to Americans’ health and safety.

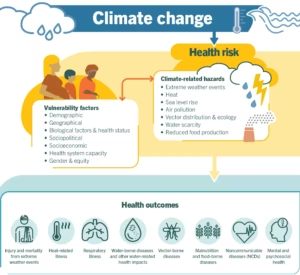

As physicians, epidemiologists and environmental health scientists, we’ve seen growing evidence of the connections between climate change and harm to people’s health. Here’s a look at the health risks everyone face from climate change.

Extreme heat

Greenhouse gases from vehicles, power plants and other sources accumulate in the atmosphere, trapping heat and holding it close to Earth’s surface like a blanket. Too much of it causes global temperatures to rise, leaving more people exposed to dangerous heat more often.

Most people who get minor heat illnesses will recover, but more extreme exposure, especially without enough hydration and a way to cool off, can be fatal. People who work outside, are elderly or have underlying illnesses such as heart, lung or kidney diseases are often at the greatest risk.

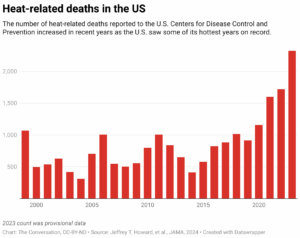

Heat deaths have been rising globally, up 23% from the 1990s to the 2010s, when the average year saw more than half a million heat-related deaths. Here in the U.S., the 2021 Pacific Northwest heat dome killed hundreds of people.

Climate scientists predict that with advancing climate change, many areas of the world, including U.S. cities such as Miami, Houston, Phoenix and Las Vegas, will confront many more days each year hot enough to threaten human survival.

Extreme weather

Warmer air holds more moisture, so climate change brings increasing rainfall and storm intensity and worsening flooding, as many U.S. communities have experienced in recent years. Warmer ocean water also fuels more powerful hurricanes.

Increased flooding carries health risks, including drownings, injuries and water contamination from human pathogens and toxic chemicals. People cleaning out flooded homes also face risks from mold exposure, injuries and mental distress.

Climate change also worsens droughts, disrupting food supplies and causing respiratory illness from dust. Rising temperatures and aridity dry out forests and grasslands, making them a setup for wildfires.

Air pollution

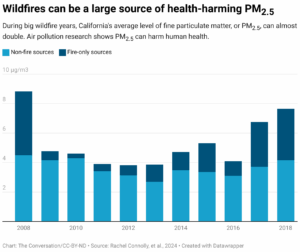

Wildfires, along with other climate effects, are worsening air quality around the country.

Wildfire smoke is a toxic soup of microscopic particles (known as fine particulate matter, or PM2.5) that can penetrate deep in the lungs and hazardous compounds such as lead, formaldehyde and dioxins generated when homes, cars and other materials burn at high temperatures.

Smoke plumes can travel thousands of miles downwind and trigger heart attacks and elevate lung cancer risks, among other harms.

Meanwhile, warmer conditions favor the formation of ground-level ozone, a heart and lung irritant.

Burning of fossil fuels also generates dangerous air pollutants that cause a long list of health problems, including heart attacks, strokes, asthma flare-ups and lung cancer.

Infectious diseases

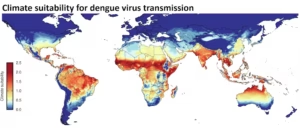

Because they are cold-blooded organisms, insects are directly influenced by temperature. So with rising temperatures, mosquito biting rates rise as well. Warming also accelerates the development of disease agents that mosquitoes transmit.

Mosquito-borne dengue fever has turned up in Florida, Texas, Hawaii, Arizona and California. New York state just saw its first locally acquired case of chikungunya virus, also transmitted by mosquitoes.

And it’s not just insect-borne infections. Warmer temperatures increase diarrhea and foodborne illness from Vibrio cholerae and other bacteria and heavy rainfall increases sewage-contaminated stormwater overflows into lakes and streams. At the other water extreme, drought in the desert Southwest increases the risk of coccidioidomycosis, a fungal infection known as valley fever.

Other impacts

Climate change threatens health in numerous other ways. Longer pollen seasons increase allergen exposures. Lower crop yields reduce access to nutritious foods.

Mental health also suffers, with anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress following disasters, and increased rates of violent crime and suicide tied to high-temperature days.

Young children, older adults, pregnant women and people with preexisting medical conditions are among the highest-risk groups. Lower-income people also face greater risk because of higher rates of chronic disease, higher exposures to climate hazards and fewer resources for protection, medical care and recovery from disasters.

Policy-based evidence-making

The evidence linking climate change with health has grown considerably since 2009. Today, it is incontrovertible.

Studies show that heat, air pollution, disease spread and food insecurity linked to climate change are worsening and costing millions of lives around the world each year. This evidence also aligns with Americans’ lived experiences. Anybody who has fallen ill during a heat wave, struggled while breathing wildfire smoke or been injured cleaning up from a hurricane knows that climate change can threaten human health.

Yet the Trump administration is willfully ignoring this evidence in proclaiming that climate change does not endanger health.

Its move to rescind the 2009 endangerment finding, which underpins many climate regulations, fits with a broader set of policy measures, including cutting support for renewable energy and subsidizing fossil fuel industries that endanger public health. In addition to rescinding the endangerment finding, the Trump administration also moved to roll back emissions limits on vehicles – the leading source of U.S. carbon emissions and a major contributor to air pollutants such as PM2.5 and ozone.

It’s not just about endangerment

The evidence is clear: Climate change endangers human health. But there’s a flip side to the story.

When governments work to reduce the causes of climate change, they help tackle some of the world’s biggest health challenges. Cleaner vehicles and cleaner electricity mean cleaner air – and less heart and lung disease. More walking and cycling on safe sidewalks and bike paths mean more physical activity and lower chronic disease risks. The list goes on. By confronting climate change, we promote good health.

To really make America healthy, in our view, the nation should acknowledge the facts behind the endangerment finding and double down on our transition from fossil fuels to a healthy, clean energy future.

Jonathan Levy is a professor and chair of the Department of Environmental Health at Boston University; Howard Frumkin is a professor emeritus of environmental and occupational health sciences at the University of Washington; Jonathan Patz is a professor of environmental medicine at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Vijay Limaye is an adjunct associate professor of population health sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. This article includes material from a story originally published Nov. 12.![]() Banner photo: The Florida National Guard responds to flooding in the Jacksonville area following Hurricane Irma in 2017 (Florida National Guard photo).

Banner photo: The Florida National Guard responds to flooding in the Jacksonville area following Hurricane Irma in 2017 (Florida National Guard photo).

Sign up for The Invading Sea newsletter by visiting here. To support The Invading Sea, click here to make a donation. If you are interested in submitting an opinion piece to The Invading Sea, email Editor Nathan Crabbe.